MacTalk

March 2023

How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life

Joanna Stern and Nicole Nguyen of the Wall Street Journal have published an article (paywalled) and accompanying video that describes a troubling spate of attacks reported by individuals and police departments aimed at iPhone users that may involve hundreds to thousands of victims per year in the United States.

Watch the video, but in short, a ne’er-do-well gets someone in a bar to enter their iPhone passcode while they surreptitiously observe (or a partner does it for them). Then the thief steals the iPhone and dashes off. Within minutes, the thief has used the passcode to gain access to the iPhone and change the Apple ID password, which enables them to disable Find My, make purchases using Apple Pay, gain access to passwords stored in iCloud Keychain, and scan through Photos for pictures of documents that contain a Social Security number or other details that could be used for identify theft. After that, they may transfer money from bank accounts, apply for an Apple Card, and more, all while the user is completely locked out of their account.

And yes, they’ll wipe and resell the iPhone too. Almost no crimes like this have been reported by Android users, with a police officer speculating that it was because the resale value of Android phones is lower. In the video, Joanna Stern said a thief with the passcode to an Android phone could perform similar feats of identity and financial theft.

The Wall Street Journal article details three kinds of attacks, only one of which is clearly avoidable. The one that’s heavily emphasized in the article I describe above. But Stern and Nguyen also spoke to victims who were drugged—a sadly common problem—and interviewed others who were subjected to violence to reveal their code. In no case have the victims done anything wrong, and anyone who frequents bars or similar venues in urban areas should beware.

Given the high profile of the Wall Street Journal coverage, I fully expect Apple to address this vulnerability in iOS 17, if not before. The obvious solution is to require the user to enter the current Apple ID password before allowing it to be changed in Settings > Your Name > Password & Security > Change Password. That won’t block access to iCloud Keychain, but at least it would let the user wipe the iPhone.

Apple probably hasn’t prompted for the current Apple ID password in the past because the passcode is considered a secure second factor—you have the iPhone, and you know the passcode. In contrast, when you log in to the Apple ID site to manage your account, you must provide your current password, go through two-factor authentication, and enter the current password again to change it. It seems like an easy change to make, at least until Apple has had a chance to think through other options.

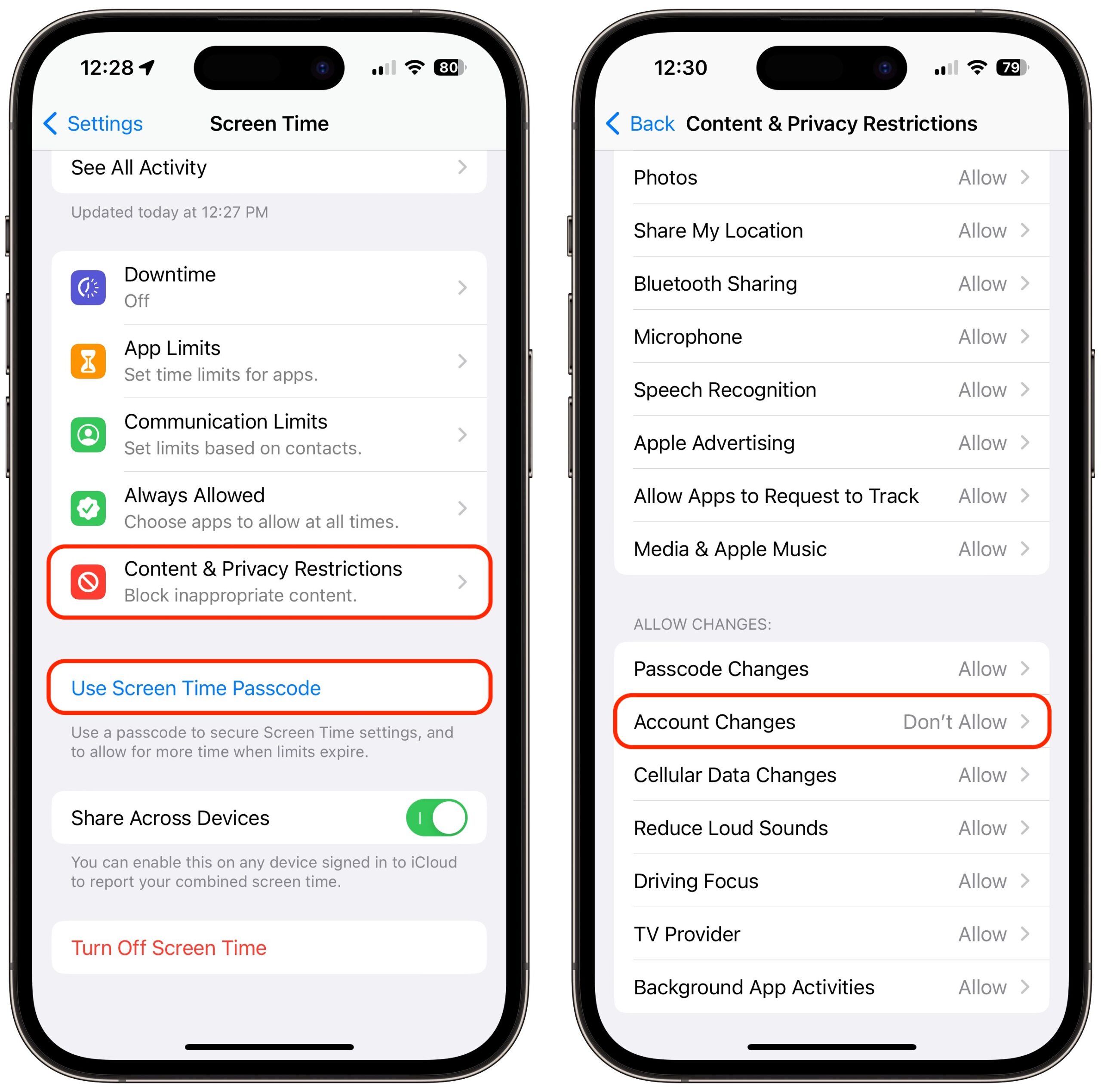

The closest we have to an additional password step is a Screen Time passcode. If you enable Screen Time, set a separate four-digit Screen Time passcode, turn on Content & Privacy Restrictions, and select Account Changes > Don’t Allow, no one can change your Apple ID password without that passcode. Unfortunately, it prevents you from even entering Settings > Your Name without first going to Settings > Screen Time > Content & Privacy Restrictions > Account Changes > ####> Allow. Most people wouldn’t put up with such a speed bump.

Another flaw that Stern and Nguyen note is that Apple’s new hardware security key option, if enabled, doesn’t always prompt for the hardware key when making changes if the user has the device passcode (see “Apple Releases iOS 16.3, iPadOS 16.3, and macOS 13.2 Ventura with Hardware Security Key Support,” 23 January 2023). The security key protection can be entirely removed, too, without having one of the hardware keys. Apple should re-evaluate how this high-security option—albeit one only a subset of users will employ—lives up to its promises.

How to Protect Yourself

You might think you would never be the victim of a watch-snatch-and-grab theft, being drugged at a bar or on a date, or a violent crime. But the theft of a passcode can happen in other circumstances. And it has such severe consequences, as the Wall Street Journal reporters noted, that even if you’re not a barfly or live in an area with a high incidence of violent property theft, I think everyone should take stock of these ways to deter malicious use of their passcode:

- Pay attention to your iPhone’s physical security in public. These attacks require both your passcode and physical possession of your iPhone. Many of us have become blasé about exposing our iPhones in public because we use them constantly and because everyone else has smartphones as well. Apple has also done a great job with the message that an iPhone is useless to a thief due to a passcode protecting its contents and Activation Lock ensuring it can’t be resold intact—this probably makes us less concerned about its security even if there’s a hassle and expense in replacing it. There’s no good way to prevent a thief from grabbing the iPhone from your hand when you’re using it, but if you can keep it in a pocket or purse when it’s not in use, rather than holding it or leaving it on the table in front of you, that reduces the chance that a thief will target you.

- Always use Face ID or Touch ID in public. The key to these attacks is acquiring the user’s passcode; the easy way to do that is to observe or record you entering it. If you rely entirely on Face ID or Touch ID, particularly when in public, no one can steal your passcode without you knowing. (Police believe those who are drugged while drinking have their faces or fingers used, but that doesn’t reveal their passcodes.) If you have been avoiding Face ID or Touch ID based on some misguided belief about the security of your biometric information, I implore you to use it. Your fingerprint or facial information is stored solely on the device in the Secure Enclave, which is much more secure than passcode entry in nearly all circumstances. If you are one of the few people for whom Face ID or Touch ID works poorly, conceal your passcode from anyone who might be watching, just as you would when entering your PIN at an ATM.

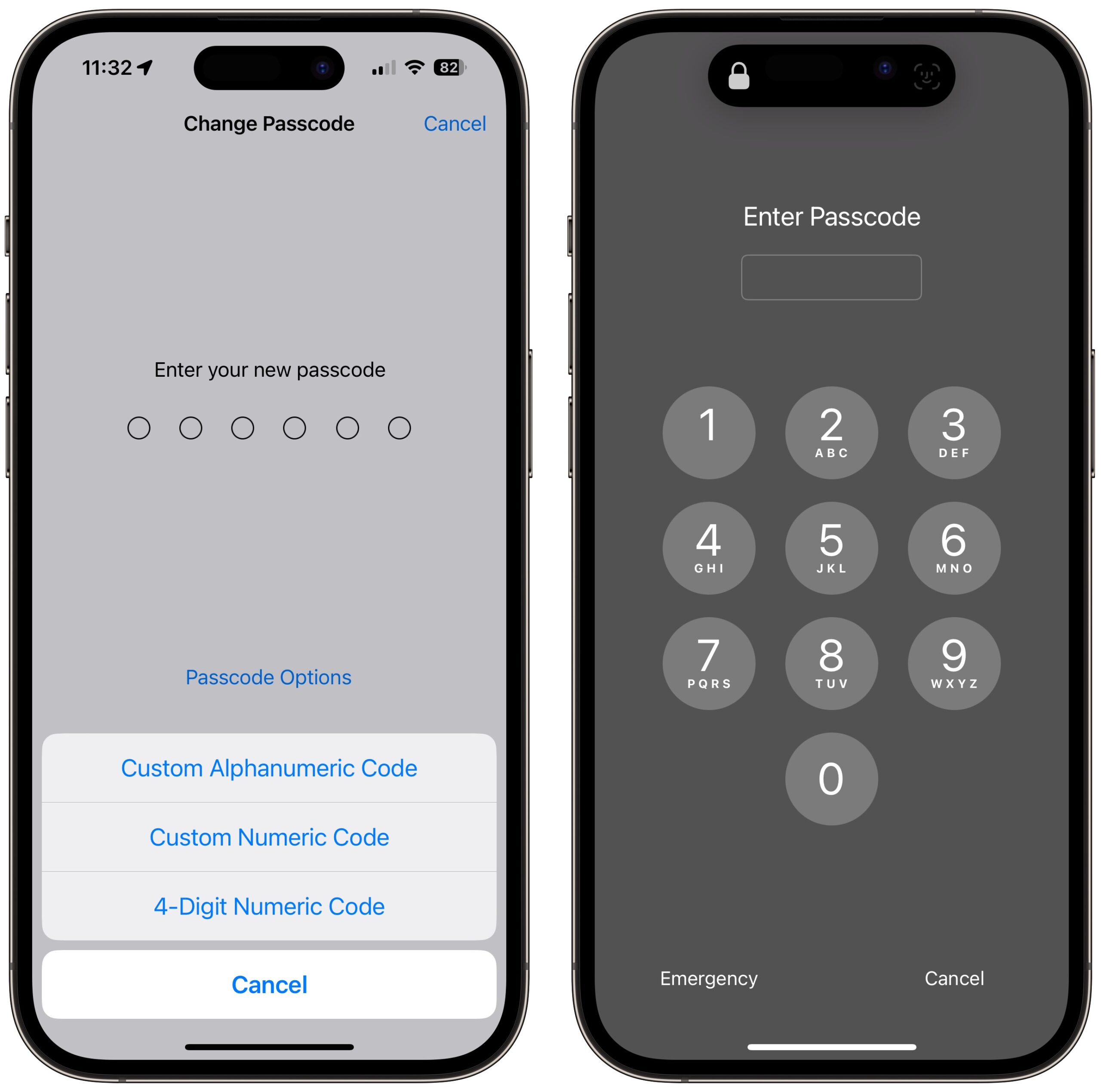

- Consider a stronger passcode: By default, iPhone passcodes are six digits. You can downgrade to four digits, which is a bad idea, but you can also upgrade to a longer alphanumeric passcode. In the video, Joanna Stern recommends that, and it might make it harder for someone to observe surreptitiously, but I’m unconvinced the increased security would be worth the added effort. Someone could still record you entering your alphanumeric passcode, and the longer and harder it is to enter, the more time it will take and the more focused you will be on typing it correctly, making you less aware of your surroundings. (Interestingly, if you set an alphanumeric passcode with just digits, you still get a numeric keypad to enter it, whereas if you add non-numeric characters, you have to use the full keyboard.) Still, I can’t recommend most people go beyond a standard six-digit passcode. Just make sure it’s not something trivially easy to observe or guess, like 111111 or 123456.

- Never share your passcode beyond trusted family members. If you wouldn’t give someone complete access to your bank account, don’t give them your passcode. If extreme circumstances require you to trust a person outside that circle temporarily, change the passcode to something simple they’ll remember—even 123456—and change it back as soon as they return your iPhone.

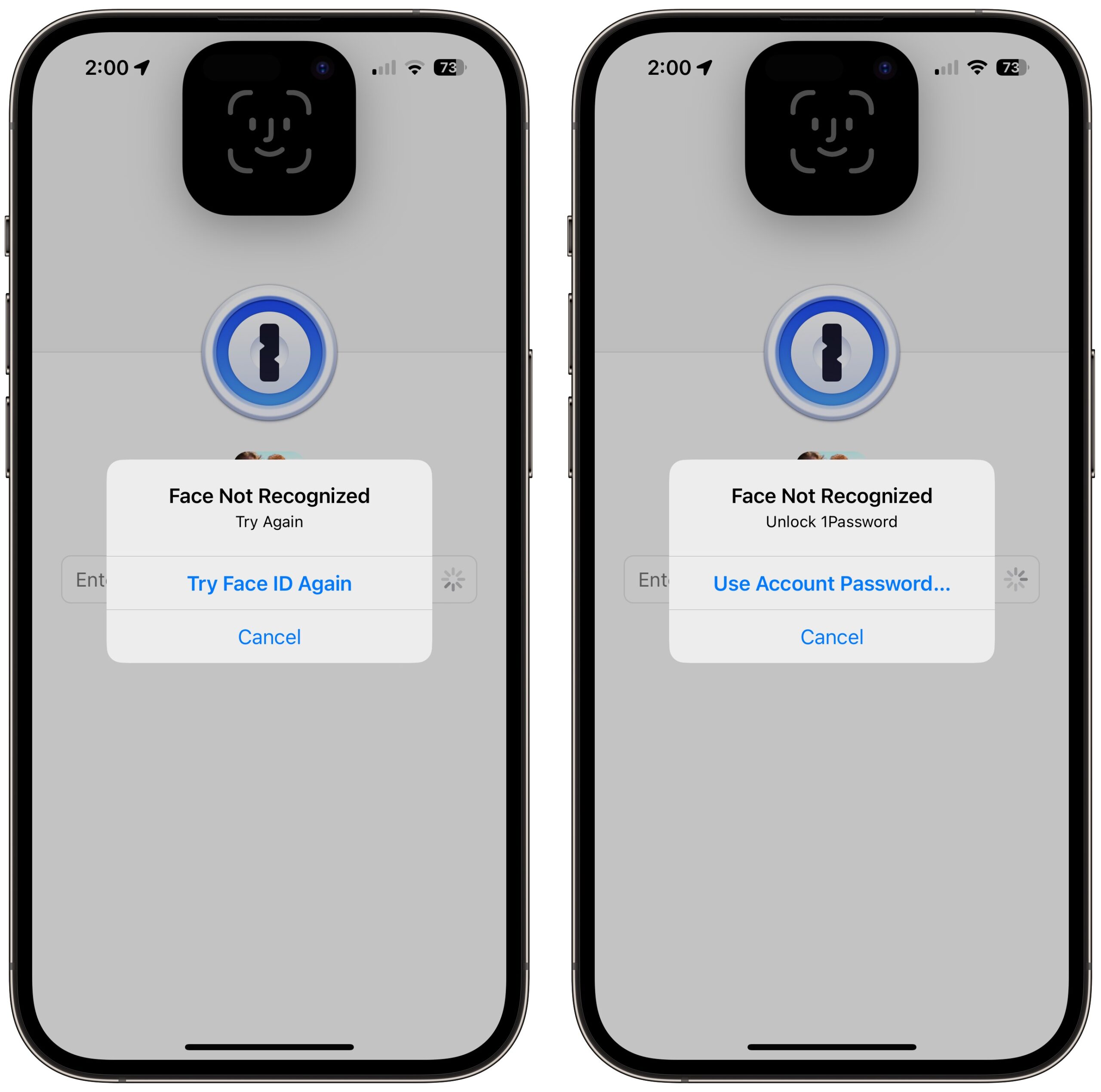

- Use a third-party password manager instead of iCloud Keychain. It pains me to recommend this option because Apple keeps improving the interface to iCloud Keychain with Settings > Passwords and System Settings/Preferences > Passwords. But until the operating systems protect access to iCloud Keychain passwords with more than the passcode, relying on iCloud Keychain is just not safe enough. In contrast, third-party password managers secure your passwords with a separate password. Even if they support and you enable biometric unlocking, the fallback is the password manager’s account password, not the device passcode.

- Delete photos containing SSNs or other identification numbers.It’s common to take a photo of your Social Security card, driver’s license, or passport as a backup, just in case you lose the real thing. That’s not a bad idea, but storing such images in Photos leaves them vulnerable to these attacks. Instead, store them in your password manager. Search in Photos on

SSN,TIN,EIN,driver’s license, andpassport, along with your actual Social Security and other identification numbers. Also search onVisa,MasterCard,Discover,American Express, and the names of any other credit cards you might have photographed as a backup. (Searching for text in Photos works in macOS 13 Ventura and iOS 16. For older operating system versions, try Photos Search; see “Work with Text in Images with TextSniper and Photos Search,” 23 August 2021.)

My Response

I’m putting my time where my mouth is. Even though I’m at a very low risk for these attacks, which primarily target bar-goers in large cities and people in areas with frequent street crime, I’ve taken steps to reduce my exposure.

First, I already rely on Face ID whenever possible, and I’ll be even more aware of who’s watching while entering my passcode if Face ID fails and I’m forced to tap in my secret digits. I’m already slightly embarrassed to have my iPhone out when I’m in public when I’m not using it, and I’ll probably keep it in my pocket even more than I used to.

Second, I decided to clear out all my iCloud Keychain-stored passwords. On my MacBook Air, I went to System Settings > Passwords, selected all of them, and pressed Delete. (You can also do this in Safari’s Passwords settings pane.) Because I have never seriously used iCloud Keychain, this was no hardship—everything in there was essentially random. Until recently, I used LastPass, but after LastPass’s breach, I switched to 1Password and imported all my LastPass passwords (see “LastPass Shares Details of Security Breach,” 24 December 2022). I had a lot of passwords already stored in 1Password from various imports and tests over the years, plus the vaults I share with Tonya and Tristan. Whenever I use a password now, I take a few minutes to clean up duplicates and related cruft, like leftover autogenerated passwords.

I realize those who rely on iCloud Keychain won’t be comfortable deleting their passwords, but I can say that I found it simple to switch to 1Password from LastPass, and 1Password offers instructions for exporting iCloud Keychain passwords and importing into 1Password. Do the export/import dance and live with 1Password—or whatever password manager you choose—for a week or two to make sure it’s working for you before deleting everything from iCloud Keychain. If you decide to return to iCloud Keychain in the future, that’s possible too.

Third, I visually browsed and used text searches in my Photos library for identification cards and the like, exporting a few for import into 1Password and deleting everything afterward. (Remember that Photos stores deleted images in the Recently Deleted album for about 30 days before deleting them permanently. To remove them immediately, select the photos in that album and hit Delete.) I found my driver’s license, passport, credit cards, insurance cards, and other cards from my wallet. Make sure to click See All after performing a Photos search if there are more than a handful of results. I even searched on card and scrolled through 500-odd photos to find a few that escaped other searches. (Who knew I took so many photos containing cardboard?)

I briefly considered moving those sensitive images to the Hidden album in Photos and using the new iOS 16/Ventura option to protect that album with Face ID or Touch ID. Unfortunately, when I tested multiple Face ID failures on my iPhone, I was eventually prompted for my passcode, which revealed the Hidden album. It’s another example of how the passcode is the key to your kingdom.

While the chance of any given person falling prey to this sort of attack is vanishingly small, and I’m not actually worried for myself, the Wall Street Journal reporting led me to think about and clean up my broader security assumptions and behavior. I appreciated the nudge, and I’d encourage you to reflect on your security situation as well.

Website design by Blue Heron Web Designs