MacTalk

September 2022

How to Securely Erase a Mac’s SSD or Hard Drive

Over on TidBITS Talk, user Lucas043 posed a question that prompted a fascinating discussion. Lucas043 has a Samsung Portable T7 SSD being used for backup. The SSD has intermittent access problems and is still under warranty, so it could be returned with no problem, but it contains sensitive client data. Lucas043’s question: What’s the most secure way of erasing the drive?

There are multiple answers to this question, but not all may be appropriate for a drive that’s being returned under warranty. Others may be perfect if you want to erase an SSD or hard drive securely but have different goals for the drive afterward.

It’s also worth considering what you think “securely” should mean. Do you want to prevent someone from recovering the files with off-the-shelf software? Are you concerned that a company like DriveSavers could extract the chips or attach new controllers? Do you worry about a government-level agency reconstructing the data?

Let’s go through the possibilities.

Destroy the Drive

The simplest way of ensuring that no one could ever read the data on an SSD is to don some eye protection and hit it repeatedly with a hammer. That’s quick, effective, and satisfying, but it does present a problem when trying to return the drive under warranty. Samsung probably doesn’t cover SSDs that come back in numerous small bits. Of course, you must physically destroy the chips inside the SSD, so make sure they’ve been thoroughly smashed.

With a hard drive, a hammer would have a similar effect, though you would want to make sure you damaged the actual platters, which is best done by drilling several holes in them. I recently did this for some elderly friends with a few old drives and a dead Mac mini (see “Helping Senior Citizens Reveals Past Apple Lapses and Recent Improvements,” 24 June 2022).

If you’re concerned about government-level extraction, drilling holes in a hard drive might not be sufficient. For that, a degausser would be more effective, or you could open the drive, remove the platters, and destroy their surfaces with sandpaper or something abrasive. There are also shredders that can eat drives, but these and degaussers are mostly appropriate for IT departments that have to decommission numerous drives containing sensitive information.

For normal people, once you’re done destroying your drive, take the remnants to an electronics recycling center in your area. When I did that, I winced when the guy who took the 2010 iMac and Cinema Display from me tossed them across the loading bay into a large bin. They were dead, of course, but still—Macs aren’t generally something that one throws.

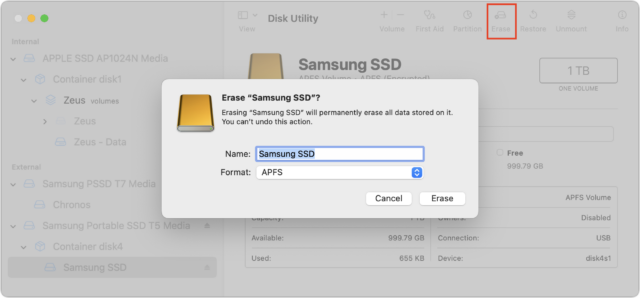

Erase the Drive with Disk Utility

The most obvious way of erasing a drive is to select it in Disk Utility and click the Erase button. Disk Utility will unmount the drive, delete the directory that keeps track of which blocks are used by which files, and create a new directory. In other words, none of the data is actually being erased; all that’s disappearing are the pointers to the storage blocks where the data is located. No directory, no access to the data.

That’s fine if you plan to reuse the drive yourself or give it to someone you either trust or don’t believe could ever muster the technical know-how to recover data from the erased drive. Or, more realistically, it’s also sufficient if your data isn’t that sensitive.

However, a simple erase in Disk Utility won’t pass muster for those concerned about security. Some apps can scan the blocks of a drive and recreate the directory, enabling file recovery. Particularly if the drive could be scanned for data shortly after being reformatted, before new data has been written over the previously used blocks, you have to assume that even a relatively non-technical person could recover much of the data.

Secure Erase the Drive Using Disk Utility

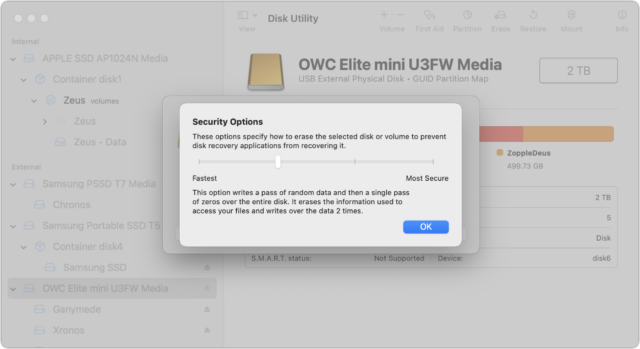

The solution to the previous approach’s limitation may seem obvious: write random data and zeroes to every block on the drive during the formatting process. That way, no recovery software can read the data that remains behind after the directory has been deleted. Disk Utility makes this easy: select the drive, click Erase, and in the dialog that appears, click Security Options and choose how many passes of random data and zeroes it should write.

Apple describes the options well but doesn’t point out that the more passes, the longer the process. I’ve never tried a seven-pass erase, but it could take days to complete on a sufficiently large drive:

- Fastest; Not Secure: This option does not securely erase the files on the disk. A disk recovery application may be able to recover the files.

- Two-Pass: This option writes a pass of random data and then a single pass of zeros over the entire disk. It erases the information used to access your files and writes over the data two times.

- Three-Pass: This option is a DOE-compliant three-pass secure erase. It writes two passes of random data followed by a single pass of known data over the entire disk. It erases the information used to access your files and writes over the data three times.

- Most Secure; Seven-Pass: This option writes multiple passes of zeros, ones, and random data over the entire disk. It erases the information used to access your files and writes over the data seven times.

Beyond the time involved, there are some additional caveats.

First, the Security Options button shows up only when it’s appropriate to use. One practical upshot of that is that you must select a drive—not a volume—in Disk Utility’s sidebar before clicking Erase because volumes don’t use all the blocks on a drive. If you’re worried about security, you want to be sure that all the blocks have been zeroed out.

Second, data could remain on a drive after a secure erase, thanks to the automatic swapping of bad blocks for good ones. If a block goes bad, the controller swaps it for a good one on the fly. If you then erase the drive, only the replacement good block will be erased, potentially leaving sensitive data on the bad block. Only a highly capable outfit like DriveSavers or a government-level agency could conceivably retrieve the data, but it’s not inconceivable. Nor is there any way of knowing what would be in those bad blocks.

Third, the Security Options button is available only when you’re reformatting a hard drive, not an SSD. Here’s why (thanks to David C. for this explanation and a lot of the great detail in the TidBITS Talk discussion). For technical reasons beyond the scope of this article, there is no direct relationship between the logical data blocks that software (including macOS) accesses and the physical data blocks in the SSD’s flash chips. The SSD controller’s firmware (on an SSD’s circuit board or in a Mac’s Apple silicon processor or T2 chip) maintains a database that maps logical blocks to physical blocks.

When you write to an SSD and the logical blocks you’re writing to already contain data, the SSD controller doesn’t overwrite the corresponding physical blocks (again, for technical reasons beyond the scope of this article). Instead, it writes the data to new, unused physical blocks, changes the logical-to-physical mapping database, and marks the previously used physical blocks as “garbage.”

Garbage blocks are not accessible to software (they are not mapped to any logical blocks), but they still contain data that could theoretically be accessed by equipment designed to bypass the SSD controller by directly reading the chips or hacking the SSD controller’s firmware.

At some later time, the SSD controller will perform garbage collection, which erases these garbage blocks, making them available for reuse. The specific mechanism used for garbage collection and when it actually occurs depend on the firmware running in the SSD controller and will vary for different SSD brands and models. Depending on the drive’s firmware and your usage—garbage collection is usually done only when the drive is otherwise idle—garbage collection might not take place for hours or even days.

This is why a secure erase is considered unreliable when used on an SSD. The act of writing random data to every logical block guarantees that all the physical blocks with your real data will be marked as garbage and therefore be inaccessible by software, but it does not guarantee when those garbage blocks will be collected and erased. If you plan on disposing of the drive, you have no way to know if the garbage data was collected before you last disconnected it from power. Apple’s removal of the Security Options button when erasing an SSD is an acknowledgment that it’s not sufficiently secure.

Still want to perform a secure erase of an SSD? You can do so from the command line, using the diskutil command.

- Run

diskutil listto determine the identifier of the drive in question. You’ll need to parse through the results to find the desired drive. - Use something like

diskutil secureErase 1 disk3to erase the drive, after which you’ll need to repartition it in Disk Utility before using it again. The 1 in the command above is for a single-pass zero fill erase, but if you readman diskutil, you’ll see all the other options, including the excessive-sounding Gutmann algorithm 35-pass erase.

If you’re not comfortable with the command line, this isn’t the time to experiment. Even then, I’m going to recommend that you avoid this technique, partly because it’s conceivable you could mistype the drive identifier and erase the wrong drive, but mostly because Apple includes a strongly worded note warning against it:

NOTE: This kind of secure erase is no longer considered safe. Modern devices have wear-leveling, block-sparing, and possibly-persistent cache hardware, which cannot be completely erased by commands. The modern solution for quickly and securely erasing your data is encryption. Strongly-encrypted data can be instantly “erased” by destroying (or losing) the key (password), because this renders your data irretrievable in practical terms. Consider using APFS encryption (FileVault).

We’ll get to encryption next, but some have wondered if there’s a way to create a huge device-filling file that would fill all the blocks with data. Alas, that’s almost exactly the same as using diskutil secureErase, so while it will probably clean out most data, it’s impossible to know what will happen with garbage collection. Don’t waste your time.

Encrypt the Drive, Then Erase It

The real solution to this problem is encryption. The ideal scenario involves enabling encryption on a drive before you do anything else with it, such that all data written to the drive is encrypted. When you later erase the drive, the encryption key will be destroyed along with the directory, rendering the data unreadable even if someone at the level of DriveSavers or a government agency were able to extract the data spread across the drive’s blocks.

How you do this depends on whether you’re encrypting your Mac’s startup drive or an external drive:

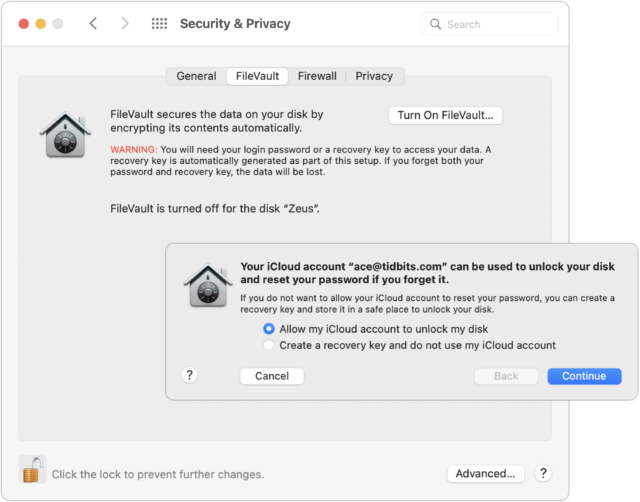

- Startup drive: To encrypt your Mac’s startup drive, turn on FileVault. Go to System Preferences > Security & Privacy > FileVault and click Turn On FileVault. You’ll get a dialog asking if you’d prefer to be able to unlock your drive using your iCloud account or use a recovery key. My feeling is that either is fine, but both are vulnerable to the xkcd wrench attack—I use the iCloud account approach.

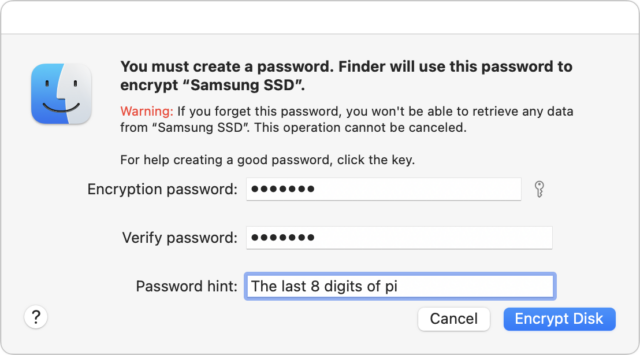

- External drive: FileVault protects only the startup drive; for external drives, take advantage of the APFS support for encryption. Control-click the drive in the Finder and choose Encrypt. You’ll be asked for a password and a hint, and macOS will help you pick a strong password if you like, though I’m pretty comfortable with the one in the screenshot. The next time you mount the drive, you’ll be asked for the password and given the opportunity to store it in your keychain so you don’t have to enter it manually again.

It’s worth keeping some facts in mind before doing all this.

- It’s quick and easy to turn FileVault on and off if you’re using a Mac with Apple silicon or an Intel-based Mac with a T2 chip. In that case, the data on the drive is already encrypted, but a password isn’t required to decrypt the data. That encryption ensures that the flash memory can’t be removed from the logicboard and decrypted; however, anyone with access to the Mac could theoretically still access the data. Enabling FileVault ensures that your account password is necessary to decrypt the drive.

- Enabling FileVault on an older Mac, particularly one with a hard drive, will take a long time because it has to encrypt everything, rather than just changing the key to one you control. Thus, if you’re enabling encryption just so you can erase the drive securely, let it finish before you erase. The FileVault screen in the Security & Privacy preference pane displays the status.

- If you’re encrypting your Mac’s startup drive and backing up with Time Machine, you should also make sure to encrypt the Time Machine backup drive. The same goes for any other backups you make to external drives.

- Encrypting data on an external drive, particularly a hard drive containing a lot of data, may take some time.

- There’s some question as to the vulnerability of data on erased blocks if you enable FileVault or encrypt an external drive after data has been written to it. The encryption will prevent access to any current data, but we don’t know if the erased blocks might still contain data that a sufficiently sophisticated attacker could extract. My feeling is that if you have a Mac with Apple silicon or a T2-enabled Mac, there’s no worry because the data is always encrypted; some erased data might be accessible, but it would be nearly impossible to put it together and decrypt it. It’s a little more of a worry with previously erased data on a subsequently encrypted external drive, but we’re still talking about intelligence agency-level work to access it. If you’re that important of a target, you should have enabled encryption before doing anything else with the Mac or external drive.

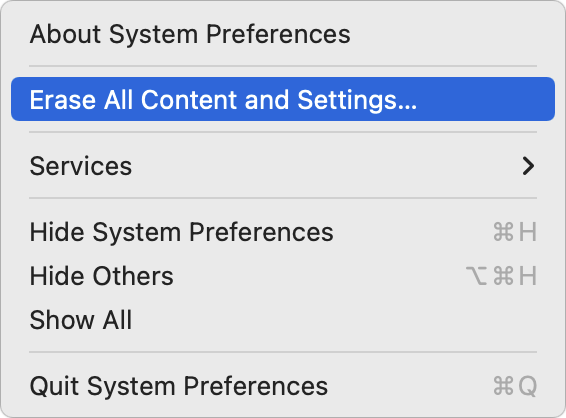

When it comes time to dispose of a Mac, you can destroy the encryption key by opening System Preferences and choosing Erase All Content and Settings from the System Preferences menu.

For an external drive, erase it in Disk Utility like any other drive. There’s no need to worry about security options because the encrypted data become random bits as soon as the encryption key is destroyed.

To make a long story short, if you think you’ll ever be concerned about erasing a drive securely, the best time to encrypt it is as soon as you start using it. If you haven’t yet turned on FileVault or encrypted a drive, the second best time to do so is now.

Contents

Website design by Blue Heron Web Designs