MacTalk

February 2024

Eight Secure Ways to Share Sensitive Information over the Internet

At some point, most of our communications switched from analog to digital: letters and phone calls transitioned to emails, texts, calendar events, and cellular, Internet, or video calls. With analog methods, we expected our secrets to remain largely safe. It was both difficult and illegal (other than for governments) to wiretap a phone line or steam open a letter. We could assume that our private communications would nearly always stay private.

The Internet made exploitation possible on a worldwide basis. No longer did someone need to pull your particular letter out of the mail stream or get physical access to a phone trunk line or switching center. Most experts underestimated how unprotected digital communications were for the longest time. It’s only relatively recently, starting over a decade ago, that the full reckoning began on what sensitive information we were unintentionally sending in the clear or storing at rest without protection, whether on our own hardware or remote server drives.

Activists, journalists, politicians, union organizers, and business executives have borne the brunt of these issues because they have a high risk of exposure revolving around what they say in private, the people with whom they’re communicating, their physical location, and their financial and medical details. Even seemingly banal conversations need to be protected because of what they could reveal, and such people should put significant thought into their communication habits and tools.

But most people and most topics don’t require strict privacy. We prefer it—we don’t want an email thread organizing dinner next week to be published for the world to see or even have it read by someone it wasn’t intended for, no matter how mundane it might be. For everyday communications, existing digital tools already provide sufficient privacy, and the consequences of any of that data being revealed are nil.

Yet, even those of us who are not high-value targets regularly need to share information that could damage our psyche, relationships, careers, or finances if it were to fall into the wrong hands or be publicly posted. Passwords are perhaps the most obvious—the entire point of them is that they’re secret, so if you have to share one, you want to make sure that only the intended recipient can access it. Once someone has a password, they may be able to view, extract, and modify all sorts of information related to you.

Protecting other kinds of data can be more challenging if they cross accounts and systems. Financial information ranks high on the list. You willingly provide your credit card information to e-commerce sites because you know—or at least expect—that they provide secure HTTPS connections and store the information with the care it deserves. But emailing your credit card details to reserve a restaurant for a group dinner feels deeply wrong. It’s probably fine most of the time, but you have no idea who can access the restaurant’s email account or if they’ll delete the message after moving the data to their payment system.

Other scenarios may involve sharing broader financial information such as bank account details, tax preparation materials, retirement planning sheets, etc. You don’t have to be attempting to hide assets to be uncomfortable with people you don’t know or outright criminals examining your assets, knowing your account numbers, and discovering other details. Whatever you think about Hunter Biden, imagine what it would be like to have the contents of your laptop extracted and displayed for all the world to see.

Then there’s health-related information. We might gripe about our aches and pains at a cocktail party but be legitimately concerned about transmitting documents relating to mental health or chronic illness through insecure channels. While it sounds quaint to talk about rivals and enemies, people face challenges in divorce, at work, and in competitive environments where exposure of private health information could be damaging.

Data at Rest and in Transit

What should you do when faced with the need to share sensitive information over the Internet? The answer depends on the nature of the information you’re sharing, the systems available to you, and the technical capabilities of the recipient. Curious about others’ approaches, I started a discussion on TidBITS Talk that generated lots of helpful advice.

Before I delve into the possibilities, consider how the information you’re sending will be protected in transit and when it’s at rest at the source and destination:

- In transit: To ensure security in transit and prevent eavesdropping, focus on communication channels that are encrypted between you and a destination.

- Between your app and a server: Nearly all the apps we use to connect to Internet services rely on HTTPS to protect connections. Such connections include both any kind of account-based resource (anywhere you maintain files or information of your own) and most information-based services (like a newspaper website). A lock in a Web browser’s address bar before a domain indicates HTTPS. You can also press Command-L in any browser and look for

httpsat the start of the URL. - End-to-end encryption: Better yet is end-to-end encryption, which ensures that not even the organization managing the service can decrypt the traffic. Encryption keys are specific to you and often locked away within each of your devices. iMessage (blue-bubble conversations in Apple’s Messages app), WhatsApp (in some configurations), and Signal (in all versions) are end-to-end encrypted. Most or nearly all of your iCloud data is also end-to-end encrypted, depending on whether you’ve enabled Advanced Data Protection (see “Apple’s Advanced Data Protection Gives You More Keys to iCloud Data,” 8 December 2022). Chat systems like Slack are encrypted, but not usually end-to-end encrypted, so your data is protected from eavesdroppers but not from employees of the service or server administrators. SMS messages (green-bubble conversation in Messages) are not encrypted at all.

- Between your app and a server: Nearly all the apps we use to connect to Internet services rely on HTTPS to protect connections. Such connections include both any kind of account-based resource (anywhere you maintain files or information of your own) and most information-based services (like a newspaper website). A lock in a Web browser’s address bar before a domain indicates HTTPS. You can also press Command-L in any browser and look for

- At rest: Data is considered at rest when it’s stored at a destination, like an SSD on your computer, your and your recipient’s mail servers, or a cloud storage service’s data center. Many services encrypt data at rest, though I don’t believe that’s common with IMAP email. Regardless, if an account is compromised, at-rest encryption is largely irrelevant. There are two ways of dealing with this concern:

- Per-file or per-message encryption: You could encrypt the data before sending so it can’t be decrypted without a password you set. This prevents someone who hijacks an email account or cloud storage account from gleaning valuable details from its content. To protect data like this, you must send the password to the recipient out-of-band: use a completely different communications channel, like a phone call or end-to-end encrypted chat. That way, someone who could access an encrypted file attachment in Gmail can’t also access the password sent in Messages.

- Time- or use-expiration: If you’re concerned about a file residing for an extended period somewhere, no matter how likely it is to be stolen, you could send a link to the information that expires after a short time. That drastically shrinks the window during which a breach could happen. Some services can also send links that can be accessed only a set number of times, rendering them useless afterward.

Solutions for Sharing Information Securely

Combining all this into a specific solution requires that you put thought into four areas:

- Audience: Who are you sharing with, and what are their technical capabilities? Email doesn’t offer the protection of encryption in transit or at rest unless you require your recipients to opt into a security system (PGP is the most common)—decades of trying haven’t made that happen broadly yet. Yet email is usually the easiest way to communicate with a technically unsophisticated recipient. Messages is easy and secure, but only when you can rely solely on iMessage, which limits its use to those who use Apple devices. WhatsApp and Signal are also fine, but only if both you and your recipient use them.

- Content: What do you want to share? Sharing a tiny bit of information like a password is different than the overhead of sharing a document, and how you share a document can vary if it can be turned into a PDF versus having to stay in a native format like a spreadsheet.

- Importance: How problematic would it be if the sensitive information you’re sharing fell into the wrong hands? There’s a world of difference between credentials to your retirement account and the password to an account that lets you edit your community center’s WordPress site.

- Persistence: How long does your recipient need the data? Do they need to glance at something and then delete it? Do they need to retain a copy permanently? While you can’t delete files from someone else’s devices, you can make sure the data doesn’t remain accessible in places used for transfers.

Here then are my recommendations:

- Secure service like DocuSign: If you’re working with a doctor, lawyer, accountant, or other professional who needs to receive sensitive information from clients regularly, they’ll often use a secure portal for messages and file transfers. It may be a custom system—many have been developed as solutions for these industries—or they may rely on a broadly available commercial offering, like DocuSign, for uploading confidential documents. Regardless, stick with whatever they require unless you have good reason to believe their IT staff is technically incompetent.

- iMessage/Signal/WhatsApp: When sharing something sensitive, there’s nothing wrong with using Messages with iMessage or an equivalently secure service like Signal or WhatsApp. (Read up on WhatsApp to ensure you aren’t exposing chat archives.) Still, I prefer to use them to share information that isn’t useful on its own. For instance, if you need to send someone a password, give them the login URL and username in email, along with any necessary instructions, but send the password separately in Messages.

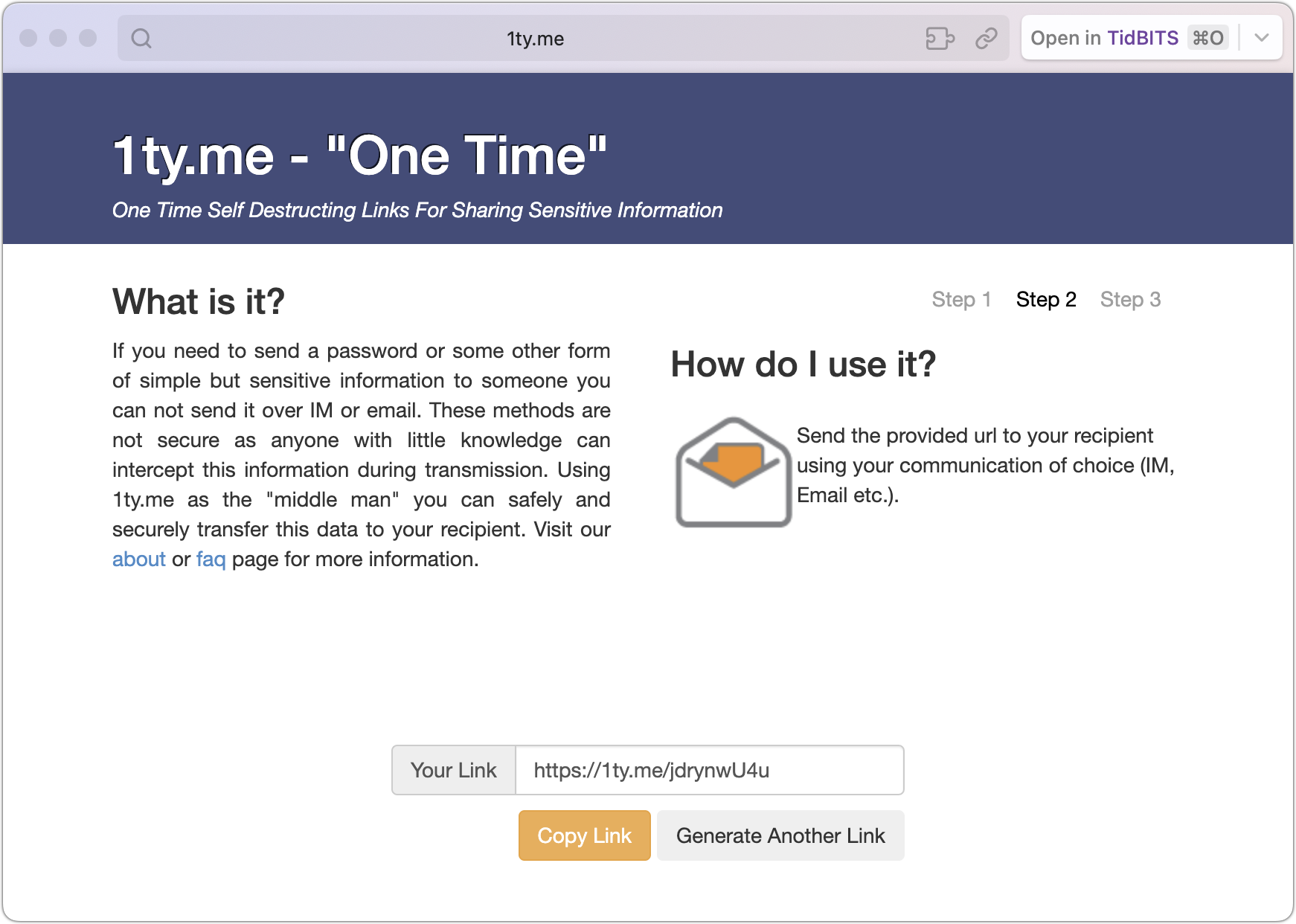

- 1ty.me or One-Time Secret self-destructing link: For sending someone a username and password to a non-critical site, I often use 1ty.me or One-Time Secret to create an encrypted link containing the text. I then share that link via email and tell the recipient to open it right away. Once they view the encrypted link, the server deletes the data, and the link self-destructs—it’s dead and can’t be used again. An attacker could eavesdrop on the communication or access the email before it was read, but if the recipient is told that the link has already self-destructed, they would know it has been compromised and can alert me. The odds are very low that anyone not in a high-risk category would ever encounter this. A more likely problem would stem from an email system that scans messages and follows links to protect against malware, causing the link to self-destruct prematurely.

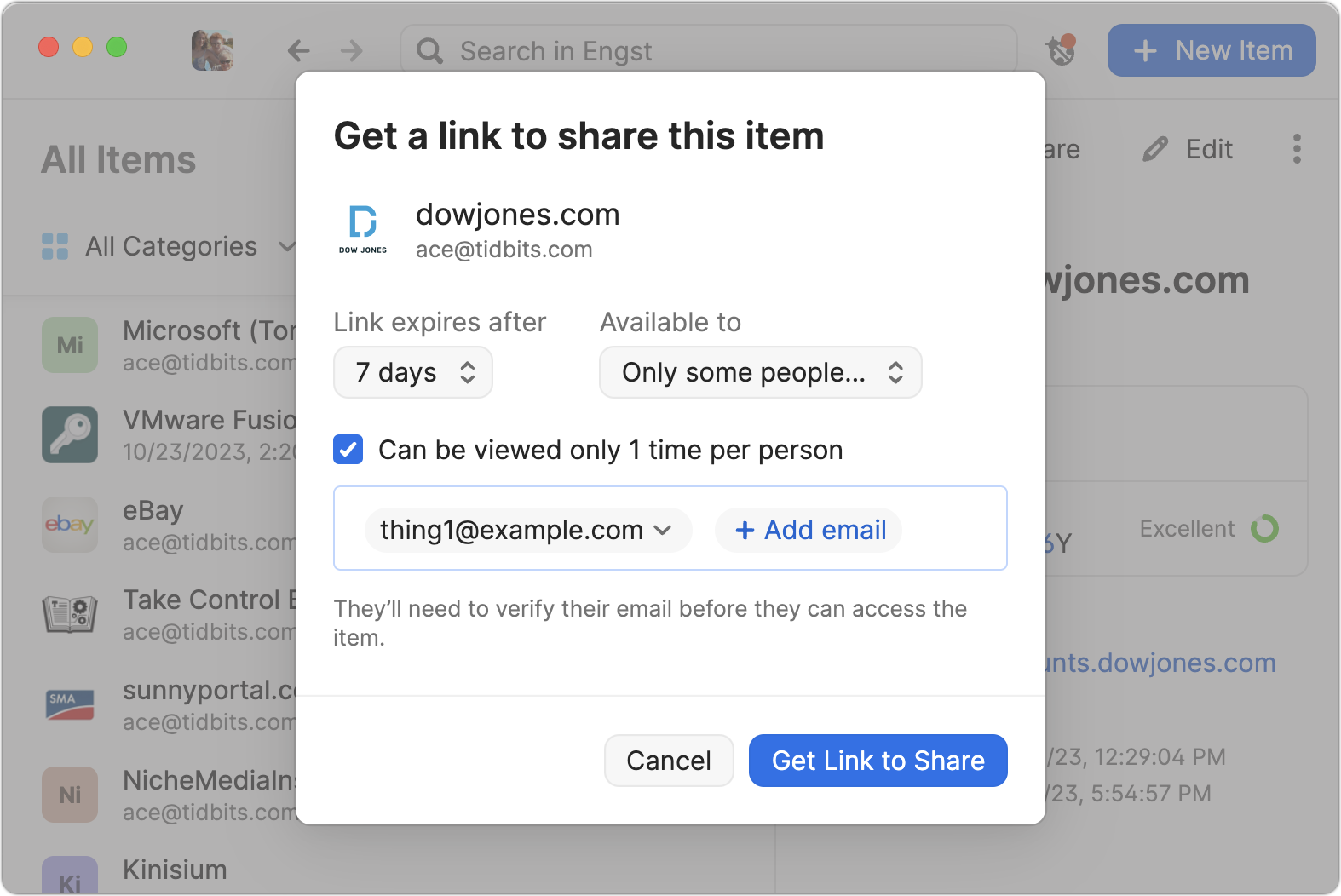

- 1Password limited link: When I need to share a password to an account I use, not one created for someone else, I use 1Password’s sharing feature to get a link like what 1ty.me creates. 1Password lets you set an expiration date, limit the link to only those whose email addresses you enter, and cause it to self-destruct after being viewed once. Other password managers may have similar sharing features.

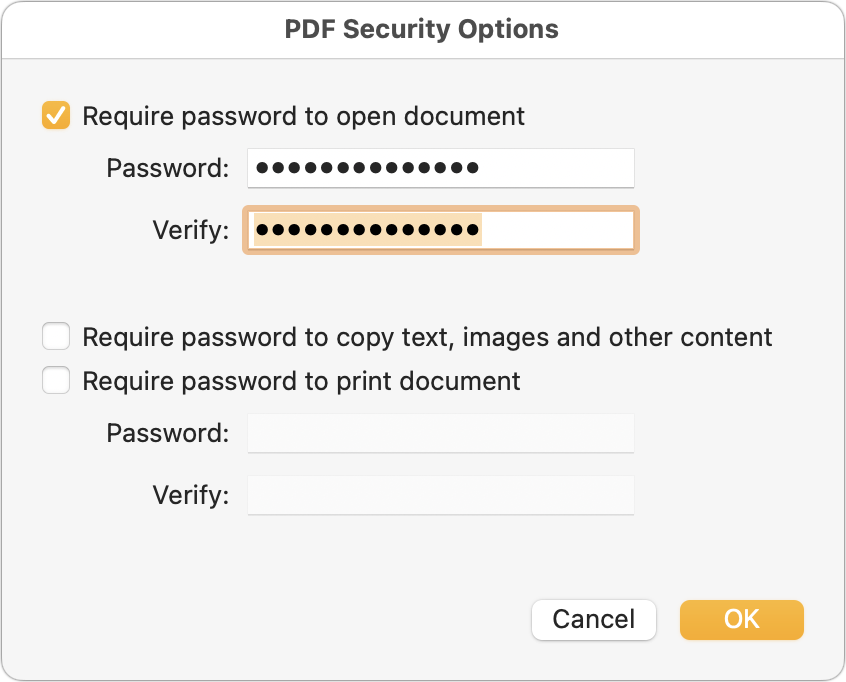

- Password-protected PDF: Sharing a sensitive document that could be printed is best done by creating a password-protected PDF. To do that from any app, choose File > Print > PDF > Save As PDF. Click the Security Options button, click “Require password to open document,” and enter a password. Creating a strong password is critical because many online services can remove weak passwords from PDFs. Save the document and share it however you like, but make sure to share the password in a different channel.

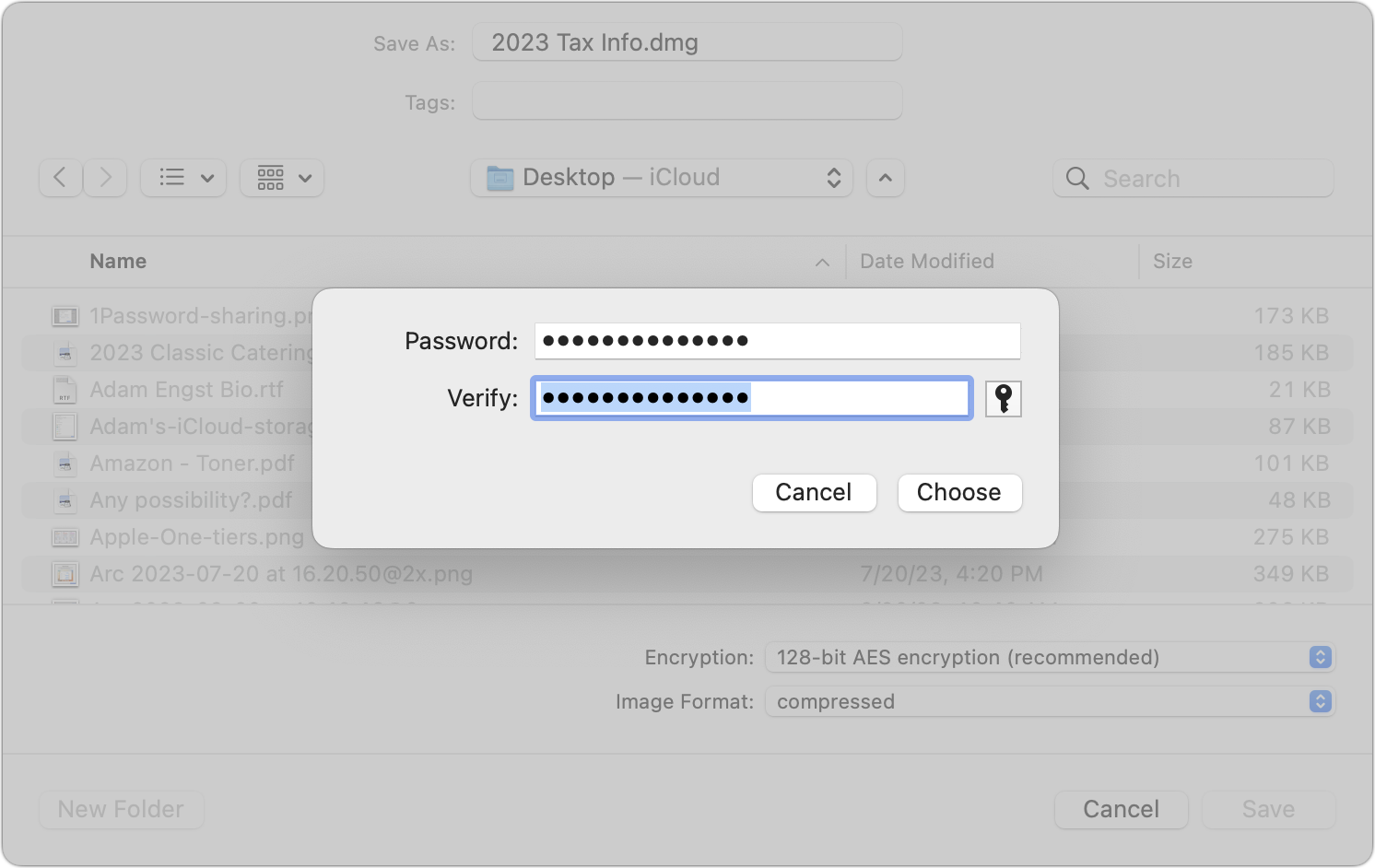

- Password-protected disk image: For files that aren’t easily turned into a PDF or to share a collection of files, creating a password-protected disk image can work well with Mac users. (Users of other platforms can open Mac disk images, but it may be difficult or require particular software or settings when creating the disk image.) In Disk Utility, create a new compressed disk image (File > New Image > Image from Folder is easiest), choose one of the two options from the Encryption pop-up menu (use 256-bit for more sensitive information), and enter a strong password when prompted. Again, share the password in a different channel.

- Password-protected Zip archive: A password-protected Zip archive serves the same purpose as a password-protected disk image and may be easier for someone using Windows or another platform to extract. When downloaded from its website (not the Mac App Store), Keka can create password-protected Zip archives for free; if you make these regularly, look at BetterZip. The fastest approach, however, is to create a password-protected Zip archive on your desktop from the command line. Follow these steps:

-

- Open Terminal.

- Type

zip -er ~/Desktop/desiredfilename.zipand press the Space bar once. - Drag the file or files you want to share into the Terminal window.

- Press Enter.

- Enter your desired password and confirm it when prompted. Type carefully; you won’t see the characters you’re entering.

-

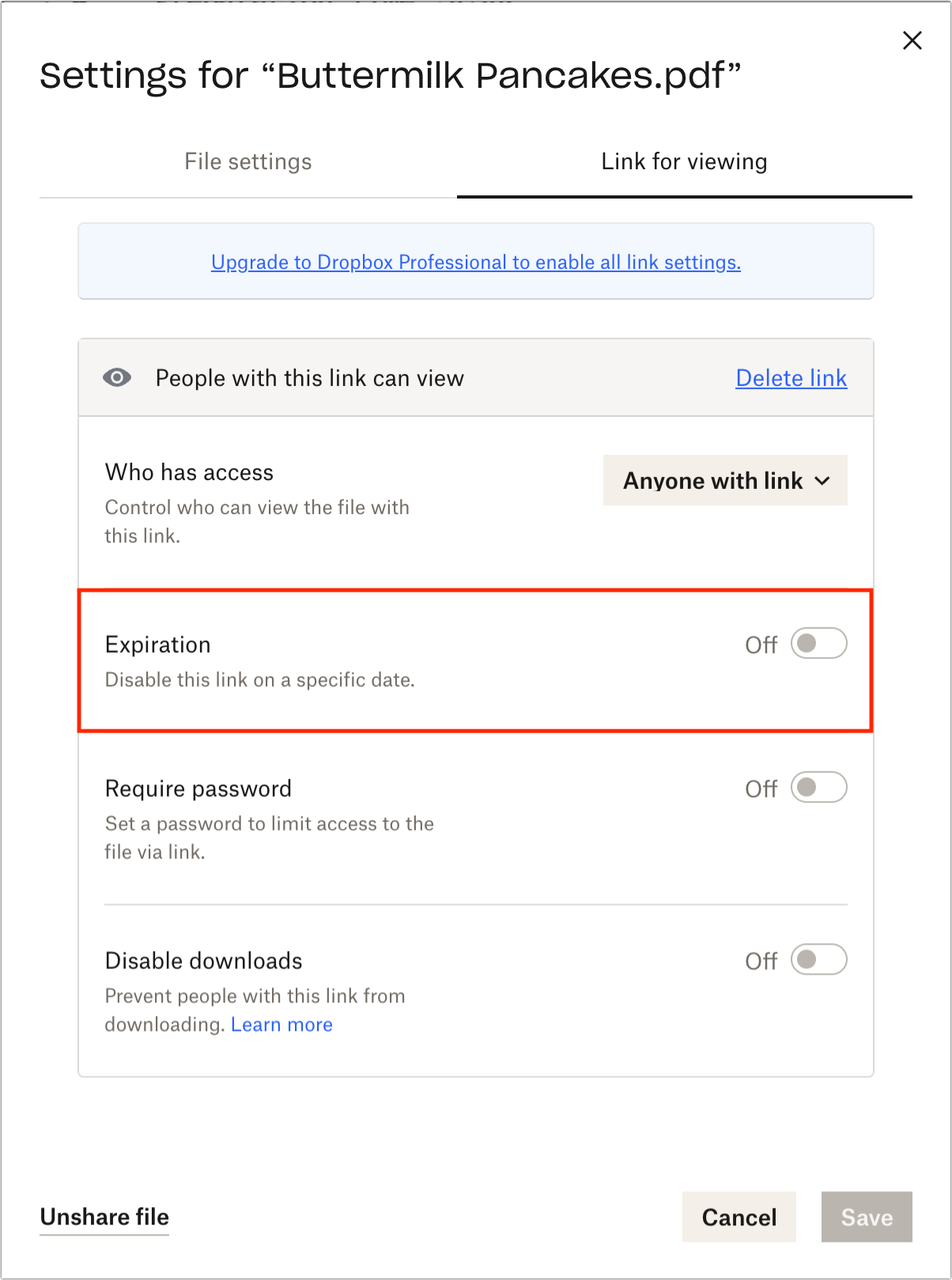

- Cloud storage link that can be expired: I don’t know how widespread this feature is, but some cloud storage services offer the option of a time-expiring link. That would enable you to share a file with someone else while ensuring the link goes away after a specified time to prevent it from being discovered in a breach and used later. Dropbox supports such links if you have a Dropbox Professional account. (Also, I haven’t used Linkly, which looks like a full-featured link-shortening service, but you could theoretically use it to create a time-expiring link that points to a shared file on a cloud storage service.)

As you can see, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to sharing information securely over the Internet. Whatever your needs are, one of the options above should suffice.

Contents

Website design by Blue Heron Web Designs