Caller ID Authentication May Tame the Scourge of Spam Calls

This morning, my iPhone rang five times. Because I pay Hiya for reverse Caller ID lookups, each number lit up with a name I didn’t know, along with the originating city and state: three from Florida and two from Connecticut. I didn’t answer any of the calls because I didn’t recognize any of the names. When I checked later, I found they lacked a relatively new indicator that I watch out for: a tell-tale checkmark. While tiny, it’s a harbinger of better things to come, particularly with a looming deadline in June 2021 for major phone carriers and Internet telephony providers.

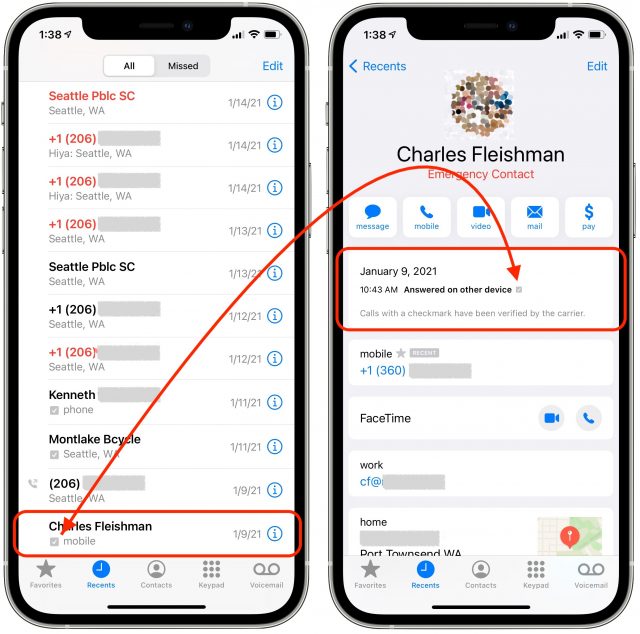

You may not even notice this checkmark—it’s truly very tiny—but it appears in the Recents list in the Phone app on an iPhone and in call details. On some Android phones, a verified indicator appears on the incoming call screen, and telephone carriers have asked Apple to add it there on iPhones, too. Only in the call detail do you get an explanation from Apple: “Calls with a checkmark have been verified by the carrier.”

What Are Those Tiny Checkmarks?

These marks started to appear in iOS 13 in the third quarter of 2019, but usage has accelerated as carriers want to block spam calls from ever reaching their customers. Spam calls cause huge headaches for those who run phone networks. They consume network resources, don’t produce revenue (spammers don’t pay a receiving phone network for the calls they place), and irritate the heck out of a carrier’s customers. Those customers, in turn, spend a lot of time complaining to customer-service operators, on forums, and to the US Federal Communications Commission and Federal Trade Commission.

Those two federal agencies have targeted these spam calls, as they want to reduce the number of people who lose money to scams. These calls might waste a moment of your time, but scammers can exploit vulnerable people in cognitive decline or those with too much trust in others to the tune of hundreds or even tens of thousands of dollars. It’s a rare regulatory initiative that started under the previous hands-off presidential administration.

These tiny checkmarks appear on calls that pass through a new standard implemented on major telephone networks starting in 2019 and gradually being rolled out by smaller ones since. The standard, known as SHAKEN, is an amusingly named expansion of an earlier plan called STIR, and the two are often spoken of together as STIR/SHAKEN. (Best said with a James Bond intonation.) What they do is establish a cryptographic chain of trust for the originating number that you see as a Caller ID message. (If you want to know what they stand for, take a deep breath: STIR is Secure Telephony Identity Revisited; SHAKEN is quite absurdly squeezed into its acronym from Signature-based Handling of Asserted Information Using toKENs.)

Larger companies involved in plain old telephone service (POTS), a loose term for the network that handles phone numbers for calling, must implement STIR/SHAKEN by 30 June 2021. There are a lot of exceptions, as noted in this industry briefing article, but any carrier with 100,000 or more lines has to be ready to go by then. (Smaller carriers have until 30 June 2023.) As we approach that date, we should see a few effects at varying levels:

- Fewer spam and scam calls: Pundits often predict this desirable result whenever there’s a major enforcement action or carriers make changes. But in the past, fraudsters just adapted because call-based financial crimes are low-hanging fruit with little risk. STIR/SHAKEN will bump up the cost of doing business, so crime won’t pay as well.

- More checkmarks: We can train ourselves and vulnerable members of our families, friends, and colleagues to identify recent calls with no checkmark. Apple might not yet put the mark on the incoming call screen, but we can check in the Recents list before treating the source as eventually legitimate. About one-third of my regular incoming calls already have a checkmark.

- Better automated call-blocking: With STIR/SHAKEN as a signal, carrier software—like T-Mobile’s free tier of ScamShield—and third-party apps could more accurately predict unwanted calls. Carriers normally are required to pass all calls placed through to a recipient, but the FCC made clear a few years ago that as long as a telco is appropriately looking for spam signals, they can block these. STIR/SHAKEN provides even more data for that purpose. (Verizon claims it has blocked nine billion unwanted calls as of December 2020 through various techniques that include STIR/SHAKEN.)

- Greater accountability: Because STIR/SHAKEN will force spammers who keep plying their trade to rely more heavily on legitimate originating phone numbers, it will make them (or their providers) a lot more vulnerable, trackable, and arrestable. It could help authorities shut down boiler-room operations much more quickly, too.

How STIR/SHAKEN Will Help

STIR/SHAKEN essentially rectifies a historical failure that resulted from extending phone system technology that assumed few participants who trusted one another, much like email. It’s harder to forge Caller ID than the return address on an email, but Caller ID has been spoofable for decades. You probably already knew that, because you’ve received so many illegitimate calls. In recent years, scammers would even engage in “prefix spam,” calling your number with a fake Caller ID number that used the same three-digit prefix that follows the area code. (That prefix remains tied to local phone exchanges with wireline numbers and regional assignments with wireless carriers.)

Originally, businesses and other institutions could set Caller ID via a PBX (corporate phone exchange), which made sense first when companies were managing oodles of internal lines and later when they started using Voice over IP (VoIP). Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when I freelanced for the New York Times, I knew I was getting a call from an editor there when Caller ID reported 1 (111) 111-1111, the number the Times spoofed to protect their internal phone numbers. (The Times changed that a decade ago.)

VoIP carriers have long had the broader capability to set a unique phone number for any outgoing call because their calls don’t originate in the plain old telephone system, and carriers had to offer that flexibility to allow Caller ID to work for VoIP calls at all. While hundreds of millions of VoIP-based calls made with correct identification occur every day, spammers also make a reported 100 million-plus illegitimate calls daily. How do you avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

A call may need to make multiple hops across different carrier and third-party networks from the caller to the person answering. STIR and SHAKEN—the latter technically an implementable and broader version of the former—use public-key cryptography to identify which phone numbers are assigned to which originating parts of the phone network. When a call is placed, it has to pass cryptographic tests that are checked at each hop and that can validate that the number identified from Caller ID originated from the right point in the phone system. (For more technical details, see my 2019 Fast Company article on the early stages of STIR/SHAKEN.)

While STIR/SHAKEN should allow carriers to block the passage of calls that lie about their originating numbers, questions remain unanswered about other elements of the system. How will it affect calls that aren’t properly tagged? How should carriers and smartphone manufacturers present such calls to the dialing public? Although Apple’s display is tremendously subtle right now, I expect more prominent marking and signaling over time, including adding a verified message to the incoming call screen. Validated Caller ID should eventually help legitimate calls evade blocking techniques that snag the unproven.

How long will this take? We can probably draw a lesson from the Web’s fairly rapid switchover from mostly non-secured HTTP sites to nearly all HTTPS-secured ones. While the transition started slowly, once browser makers decided on schedules, they began to identify sites without HTTPS with increasingly aggressive labeling that warned of the lack of security. That changeover was combined with significantly easier and cheaper systems for creating and managing the necessary security certificates, like Let’s Encrypt. Having both the carrot of easy upgrades and the stick of browser warnings prompted site owners to upgrade their security.

Ultimately, companies and carriers will find their calls dropped or blocked unless they fully embrace STIR/SHAKEN as it’s adopted by mobile phone operating systems and the rest of the phone network. For those who have built businesses on unethical practices, we hope STIR/SHAKEN will spell the end for them. Good riddance, and we look forward to the day when we can once again answer the phone without worrying that we’re being targeted by a scammer.

Contents

- Mac OS X at 20: The OS That Changed Everything

- Is It Safe to Upgrade to macOS 11 Big Sur?

- iOS 14.4.2, iPadOS 14.4.2, iOS 12.5.2, and watchOS 7.3.3 Address Serious WebKit Issue

- In Praise of the Knock-Off Nylon Sport Loop

- Caller ID Authentication May Tame the Scourge of Spam Calls

- Apple’s AirPods Max Headphones Are Pricey but Good