Mac OS X at 20: The OS That Changed Everything

Has it really been that long? 24 March 2021 marked the 20th anniversary of Mac OS X. For those of us who were there to witness its release, it’s stunning to think that most of today’s Apple users never used the “classic” Mac OS that powered the Mac from 1984 to 2001 (and beyond: some people still use it).

Former Apple executive Scott Forstall made a rare tweet to commemorate the occasion, recalling when Steve Jobs slashed an X into a wall to declare the name.

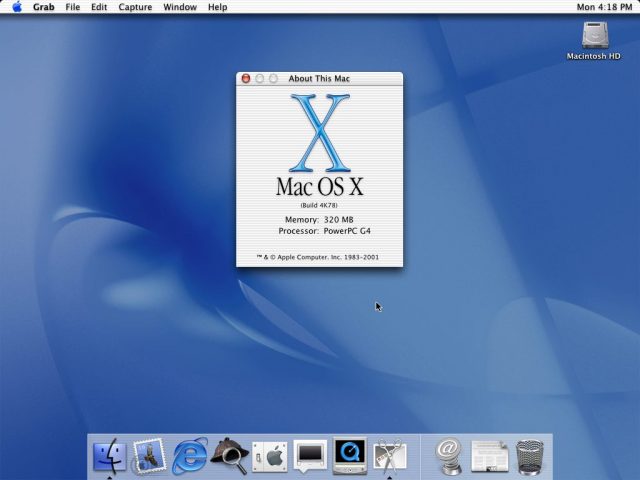

When Mac OS X (now simply called macOS) debuted in 2001, it felt like something from the future, with its photo-realistic icons and animations. Stephen Hackett maintains a gallery of screenshots from Mac OS X 10.0, and it’s amazing how well it holds up two decades later.

Mac OS X introduced concepts then foreign to Mac users, like the Dock and Terminal. As someone who lived through the transition, Mac OS X was a huge leap forward. It made not only the classic Mac OS feel dated, but also Microsoft’s competing Windows XP, which wouldn’t even ship until August of that year.

But the initial release of Mac OS X 10.0 was basically a paid beta. (It wouldn’t be until 10.9 Mavericks that it became free.) Many features of classic Mac OS were missing, app compatibility was sparse outside of Classic mode, and while the operating system felt like something out of the future, it also seemed to be waiting for future hardware. Performance was dreadful. Adam Engst documented those early rough edges in “Mac OS X: The Future Is Here – Coming Soon!” (26 March 2001), saying:

The reason for Apple’s quiet release is simple – in my opinion, Mac OS X doesn’t offer most people enough advantages over Mac OS 9. One fact is indisputable: Mac OS X can’t currently do everything that’s possible with today’s hardware and software. A number of Apple’s high-profile features are missing, such as playing DVDs and burning both DVDs and CD-Rs. Hardware is also problematic – although Mac OS X has support for some peripherals and expansion cards, using other pieces of hardware may require the user to reboot in Mac OS 9.1. (A tip – on Macs since the beige Power Mac G3, hold down the Option key when restarting to receive a choice of operating systems to use for the next startup.) And of course, although many applications run fine in Mac OS X’s Classic mode, few applications have been “carbonized” so they can run natively under Mac OS X. Luckily, among those already carbonized are Apple’s own iTunes, iMovie 2, and a preview of AppleWorks 6.1, all of which can be downloaded.

Mac OS X 10.1 followed in October 2001 with performance improvements, CD burning, and interface enhancements (see “Mac OS X 10.1: The Main Features,” 1 October 2001). That was my first version of Mac OS X, which I installed on a PowerBook G3 (Lombard).

If you’re interested in a stroll down memory lane, Jason Snell has a compilation of his Mac OS X coverage over the years, along with an overview of the changes in each version. For those with lots of free time, John Siracusa maintains links to all of his voluminous Ars Technica Mac OS X reviews, from 10.0 to 10.10 Yosemite.

Mac OS X may have had a rough start, but it created the underpinnings not only for the future of the Mac, but also for the iPhone, iPad, and even the Apple Watch. It’s arguably one of the most consequential software launches in history, but it almost didn’t happen.

A Desperate Gambit

Over at Macworld, Jason Snell has done an outstanding job of documenting the birth of Mac OS X. The original Mac OS was groundbreaking in 1984, but it aged quickly. By the 1990s, it was clear that Mac OS needed a complete overhaul, but the Apple of that era was a disaster. The most famous attempt was codenamed Copland, and you can get a sense of it on the Paul’s Crap YouTube channel.

Apple eventually realized that the best way forward was to buy a new operating system. The choice was between two companies headed by former Apple executives: Steve Jobs’s NeXT and Jean-Louis Gassée’s Be. Everyone knows how that turned out.

NeXTSTEP provided more than just Mac OS X’s Unix foundation, including key interface elements like the Dock, apps like TextEdit, and the use of Objective-C for building apps (which is now largely being supplanted by Swift). Long-time Mac developer James Thomson coded the Dock and tweeted about his nervousness at watching Jobs demo it for the first time.

Apple’s 1997 purchase of NeXT caused quite the stir. Geoff Duncan documented it for us in “What System Comes NeXT?” (6 January 1997). A few months later, Adam Engst offered some analysis of the NeXT purchase and then-CEO Gil Amelio’s decisions in “Apple’s Decisions” (31 March 1997):

One theme among the mail I’ve received about Apple’s recent changes is the perception that former NeXT employees are now making Apple’s decisions. One person even commented that it felt like NeXT had bought Apple, not the other way around. To some extent, these perceptions are accurate – after all, Avie Tevanian and Jon Rubinstein, two ex-NeXT folks, are in charge of the operating system and hardware divisions.

That turned out to be perceptive indeed, as it’s now well-documented history that NeXT took over from within. As Adam remarked at the time, “What else could Gil have done?” Gil Amelio is often cited as the worst Apple CEO, but if nothing else, he made the correct decision in purchasing NeXT and bringing back Steve Jobs, even if he didn’t realize he was putting his own head on the chopping block by doing so.

But there were questions about whether Apple would keep being Apple after being consumed from the inside by NeXT:

In essence, the acquisition of NeXT is having a significant impact on Apple’s culture. That’s not necessarily bad, but it can make for an occasionally acrimonious transition. The question is whether the attitudes and beliefs that made the Macintosh special can survive in the new atmosphere.

Apple veteran Imram Chaudhri, who is credited with much of the iPhone’s interface, among many other accomplishments, tweeted a funny anecdote about his early interactions with Jobs and how a second-hand NeXT cube helped him win many arguments with the strong-willed CEO by letting him demonstrate the operating system’s many flaws.

Beyond X

Mac OS X was the operating system’s official name until Apple dropped the “Mac” part halfway through the reign of Mac OS X 10.7 Lion (we refused to switch mid-cycle, waiting instead until 10.8 Mountain Lion). Some years later, Apple dropped the X and recast the name again with macOS 10.12 Sierra. Now with macOS 11 Big Sur, Apple has finally moved on from the 10 version number, finally giving macOS updates sensible version numbers (see “How to Decode Apple Version and Build Numbers,” 8 July 2020).

Names aside, the NeXT-derived core of Mac OS X remains, even through architectural transitions from PowerPC to Intel and now from Intel to Apple silicon. And while a few apps from the early days are no more, many of the original Mac OS X applications remain, like the underappreciated and surprisingly powerful Preview.

The original Mac OS had an official run of 17 years, and the descendants of Mac OS X 10.0 are still going strong 20 years after its introduction, with no end in sight. What was once a desperate attempt by a flawed CEO to save a dying company has blossomed into a $2 trillion ecosystem.

Contents

- Mac OS X at 20: The OS That Changed Everything

- Is It Safe to Upgrade to macOS 11 Big Sur?

- iOS 14.4.2, iPadOS 14.4.2, iOS 12.5.2, and watchOS 7.3.3 Address Serious WebKit Issue

- In Praise of the Knock-Off Nylon Sport Loop

- Caller ID Authentication May Tame the Scourge of Spam Calls

- Apple’s AirPods Max Headphones Are Pricey but Good