Is it time to upgrade to macOS 11 Big Sur? I’ll write more about that soon. However, there is one general concern that has caused us to hesitate to recommend upgrading. That’s the complexity of creating a bootable duplicate of your startup volume, also known as a clone. To understand why this seemingly simple task—just read all the data from one drive and write it to another—is causing such consternation, we need to step back briefly. And once we’ve done that, we can reassess the role of a bootable duplicate in a modern backup strategy.

Why Bootable Duplicates Have Become Difficult to Make

In 10.15 Catalina, Apple introduced APFS volume groups, a way of bundling separate volumes together to create a bootable macOS. A System volume holds all the files macOS needs to operate, while the Data volume contains only your data. The two volumes appear as a single entity in the Finder and wherever you might select or navigate files. The System volume is also read-only, so malicious software cannot modify the operating system, whereas the Data volume that contains your files remains read-write so you can install apps and create and modify documents.

This architectural change forced backup apps that make bootable duplicates to jump through hoops, since they couldn’t just read and write data anymore. Now a bootable duplicate had to have a System and a Data volume, and they had to be combined correctly into an APFS volume group. Eventually, all the leading apps figured out how to do this: see “Carbon Copy Cloner 5.1.10” (26 August 2019), “ChronoSync 4.9.5 and ChronoAgent 1.9.3” (11 October 2019), and “SuperDuper 3.3” (30 November 2019).

With Big Sur, however, Apple went a step further, adding strong cryptographic protections when storing system content on what is now called a Signed System Volume. (In fact, Big Sur doesn’t even read files directly from this System volume to boot your Mac. It first takes the additional step of creating an immutable APFS snapshot—a reference to the volume at a particular point in time—and starts up from that snapshot. Thus, Big Sur is actually booting from a cryptographically signed, immutable reference to a cryptographically signed read-only volume.)

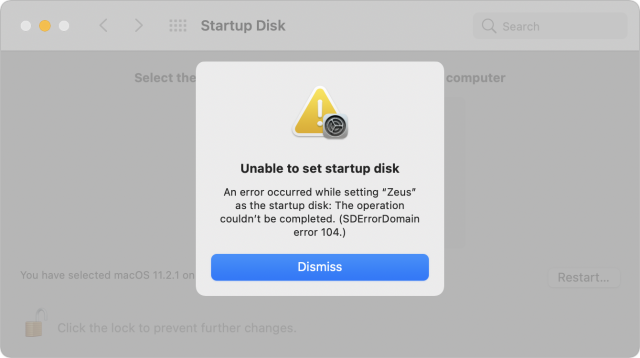

This change increases security even more, but also prevents all backup apps from creating bootable duplicates because they cannot sign the backed-up System volume. In theory, Apple’s asr (Apple Software Restore) tool makes this possible, but it didn’t work at all until just before Big Sur was released, still has problems, and even now cannot make a bootable duplicate of an M1-based Mac boot drive. On the plus side, Apple has said it plans to fix asr, but who knows when, or how completely, that will happen.

All three of the leading apps for making bootable duplicates have come up with workarounds. Carbon Copy Cloner recommends installing Big Sur onto a data-only backup after creating it, whereas ChronoSync suggests installing Big Sur on an empty drive first and then using it for your data-only backup. The current version of SuperDuper has other issues with Big Sur, so SuperDuper’s workaround involves downgrading to SuperDuper 3.2.5, using that to make a data-only backup, and then installing Big Sur on the backup drive if you need to boot from it. Unfortunately, once you do this, you can no longer copy to the backup until you delete the System volume, so it’s best to stick with SuperDuper 3.2.5’s data-only backups.

Things become even more confusing if you add an M1-based Mac into the mix. At the moment, Howard Oakley reports that you can make a bootable duplicate only onto a native Thunderbolt 3 drive—a USB drive doesn’t work reliably for the purpose. That bootable drive also won’t start up Intel-based Macs, even if you set up separate APFS containers. The reverse is true as well—an external drive that will boot an Intel-based Mac will not necessarily boot an M1-based Mac. So, even if you can make one, a bootable duplicate won’t help you unless every Mac you want to use it with uses the same chip.

Do You Need a Bootable Duplicate?

Sometimes, when the world shifts in a way that renders past approaches unsatisfying, it’s worth reexamining the base principles in play. Why have we recommended bootable duplicates as part of a backup strategy anyway? Three reasons:

- Quick recovery: The primary reason for having an up-to-date bootable duplicate is so you can get back to work as quickly as possible should your internal drive fail. Simply reboot your Mac with the Option key down at startup, select the bootable duplicate, and continue with your work. If your Mac were to die entirely, you could use the clone with another Mac you own or borrow, or a replacement that you can purchase and return within 14 days.

- Secondary backup: Any good backup strategy has multiple backup destinations, preferably created using different software. If you consider your primary backup to be Time Machine, for instance, having a bootable duplicate made with another app and stored on a separate drive protects against both potential programming errors in Time Machine and physical or logical corruption of its drive. It’s best not to put all your eggs—or backups—in one basket.

- Faster migration: I’ll admit I have no data here, but if I needed to use Apple’s Setup Assistant or Migration Assistant to migrate to a new drive or Mac, I’d prefer to use my bootable duplicate over my Time Machine backup. With Time Machine, the migration will have to figure out what the newest version of every file is, whereas the bootable duplicate is, by definition, an exact clone.

When you think about it, only the first of these reasons requires that the duplicate be bootable. A data-only backup using different software to a separate drive is sufficient for the second two.

The last time I needed to boot from my bootable duplicate was a disaster (see “Six Lessons Learned from Dealing with an iMac’s Dead SSD,” 27 April 2020). I had been backing up to a 5400 rpm hard drive connected to a 2014 27-inch iMac via USB 3.0, but using it as a boot drive was “painful beyond belief.” Since then, I’ve switched to using a Samsung T5external SSD for my bootable duplicate because its performance is so much better.

Performance isn’t the only issue here. When my internal SSD died, I spent many hours troubleshooting the problem before discovering that my bootable duplicate wasn’t going to help. I suspect that’s common—you don’t necessarily know that your internal drive is dead right away, so you’re going to try to fix it before falling back on your bootable duplicate. Quick recovery? I could easily have reformatted my internal SSD and restored from a backup in the amount of time I spent troubleshooting. In fact, I started down that road too, only to discover that I couldn’t even reformat, wasting even more time.

In the end, I got up and running with my everyday work using other devices: my 2012 MacBook Air, my 10.5-inch iPad Pro, and my iPhone 11 Pro. Most of what I do is in the cloud now, between email, Slack, Google Docs, and WordPress, so while I wasn’t as productive on the other devices as I would have been on the faster, double-monitor iMac, I could get my work done. Since then, I’ve replaced the 2012 MacBook Air with an M1-based MacBook Air with more storage and vastly better performance, so I would have even fewer issues using it as my fallback Mac.

All this is to suggest that the bootable part of a bootable duplicate is no longer as essential for many people as it was when we first started recommending that a comprehensive backup strategy should include one. Since then, it has become far more common for people to have multiple devices on which they could accomplish their work, and much more of that work takes place in the cloud or on a remote server.

The Parts of a Modern Backup Strategy

Allow me to update what I consider to be the pieces you can assemble into a comprehensive backup strategy that acknowledges the reality of today’s tech world. In order of importance:

- Versioned backup: Everyone should have a versioned backup made with Time Machine. Versioned backups are essential for being able to recover from corruption or inadvertent user error by restoring an earlier version of a file or the contents of a folder before deletion. Other backup apps, like ChronoSync and Retrospect, can make versioned backups too, but Time Machine backups are particularly useful because of how Apple integrates them into macOS migrations. I won’t pretend that Time Machine is perfect, but it’s part of macOS, has insider access to technical and security changes in macOS, and generally works acceptably.

- Internet or offsite backup: Local backups are worthless if all your equipment is stolen or damaged by fire or water. Historically, the recommendation was to rotate backup drives offsite, but in the modern world, an Internet backup service like Backblaze is much easier.

- Backup Mac or another device: Particularly given how hard it is for anyone but Apple to repair Macs, if you can’t afford days of downtime, think about both what device you could use for your work if your Mac were to fail and how you’d get your data to it. It might be a laptop you mostly use when traveling, your previous desktop Mac, or even an iPad. Just make sure to take your backup device out for a test run before you need it.

- Cloud-based access to key data: This isn’t a requirement—lots of people either can’t or don’t wish to store data in the cloud—but for many, it can be a way to access essential data from any device or location. For instance, $9.99 per month gets you 2 TB of iCloud Drive storage, and Apple’s Desktop & Documents Folders syncing feature could make it particularly easy to get back to work on another Mac. A similar amount of money would provide 2 TB storage on Dropbox, Google One, or Microsoft OneDrive.

- Nightly duplicate, data-only or bootable: Even if a duplicate can’t easily be made bootable, it’s still a worthwhile part of your backup strategy. It adds diversity by relying on different software in the event your Time Machine falls prey to bugs, by putting a backup on another drive, and by eliminating the need for special software beyond the Finder to restore data. And, of course, if you have to fall back to another Mac, a duplicate may be necessary so you can get back to work on your files.

Ensuring that you have an answer for all five options above would provide the most protection and the fastest recovery. But for many people, all five would be overkill.

I’d say that every Mac user should be making Time Machine backups, and some combination of Internet backup or cloud-based storage of data is a good idea. If your house were to burn down, wouldn’t it be nice if you didn’t lose your entire photo collection? iCloud Photos isn’t a full backup like Backblaze is, but either would ensure the survival of your irreplaceable photos and videos.

People whose livelihoods depend on their ability to meet tight deadlines might feel the need to have a relatively powerful backup Mac available at a moment’s notice, but for many of us, an older Mac or less powerful laptop might be sufficient. And for those who don’t rely on their Macs for work, an iPhone or iPad might meet all your communications needs until you can repair or replace a dead Mac.

Similarly, those who keep a lot of data in the cloud or simply don’t value their data all that highly might be willing to risk having Time Machine be their only backup.

That said, I’ll stick with my nightly duplicates because they’re just too useful for troubleshooting and recovery. But I just can’t say that bootable duplicates are the necessity they once were.

What do you think? How often have you relied on a bootable duplicate to return to work quickly after an internal drive failure? Have you been stressing about bootable duplicates in Big Sur? How would you respond to your Mac failing entirely?

Contents

- The Role of Bootable Duplicates in a Modern Backup Strategy

- How to Manage Breathe Notifications on the Apple Watch

- Ensure Sufficient Free Space before Upgrading to Big Sur

- BlastDoor Hardens iMessage Against Malware Assaults

- Apple Platform Security Guide Reveals Focus on Vertical Integration

- Add AirPlay to Your Classic Stereo with an Old Apple TV

- New Members